Rio Tinto was one of the biggest beneficiaries of China’s rapid recovery from the pandemic. In 2021 huge profits from its iron ore mining generated a $9bn cash-back to shareholders. This pay out included a record final dividend of $6.5bn.

It is old physical economy. You can’t get much older than mining as an economic activity. Mining a third of a billion tonnes of iron-rich dirt every year is not exactly at the cutting edge of technology. Copper might be the bellwether of the global economy but steel is the exoskeleton of the world’s infrastructure. – buildings, bridges, ships, and railways. And are we to make wind farms out of plastic? You need iron ore to make steel.

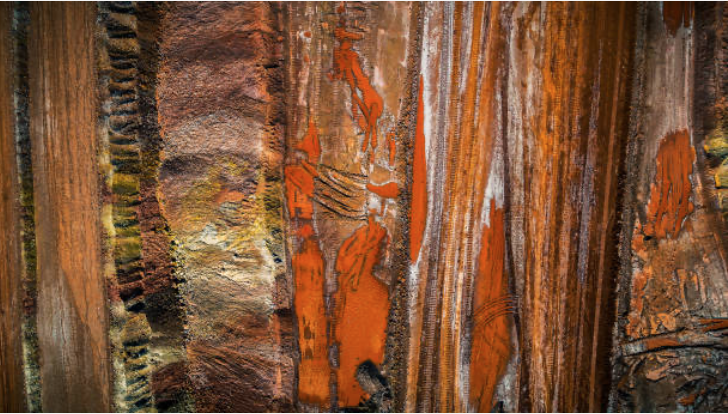

I was in the hinterland hill country of Andalucía a few months ago looking at geology in the Iberian Pyrite Belt (IPB) through an economic lens. My hosts took me on a side trip to visit the historic Mina de Riotinto. The hallowed ground of the “red river mine” . The Rio Tinto river runs over mineralised outcrops and is red with iron from weathered pyrite – an iron sulphide.

The red river has run red for eons. Mining here dates back over four thousand years to the Chalcolithic era (copper rock). Tartessians, Phoenicians and Carthaginians mined iron, silver and copper at the ancient mines of Riotinto. Mining reached its peak with the Romans and petered away with the demise of their Empire. This long history means today almost all the outcropping and near surface deposits are exhausted and mineral exploration must now target “deeper”, blind deposits.

In the late 19th century mining at Rio Tinto started again under the leadership of a Scottish mining entrepreneur. This was the start of the eponymous global mining power house called Rio Tinto. Today open pits extend over an area of about five kilometres by one and half kilometres wide.

During the day on the outcrop the temperature had reached a heavy 40 degrees Celsius. In these parched hills sparse clusters of resilient pine and eucalyptus try to get a hold. Anaemic soils form on steeply dipping Culm flysch rocks of early Carboniferous age. The town of Valverde del Camino crouches in the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada about 60 kilometres, as the crow flies, northwest of Sevilla. The population is around 12,000 inhabitants and it is known in Spain and internationally for its vaquero-style leather riding boots.

Some locals had drifted down to town centre in the lengthening shadows to take tapas alfresco–style in the plaza. There are no tourists in these parts. It is much cooler now and patrons are wafted by cooling breezes funnelled down ravines from the high mountains to the east. I was now sitting at a table facing the boutique baroque Ayuntamiento and sipping a cold Cana de Cerveza. There is a timelessness about all this. So I took to thinking about the dimensions of time and the red river. If man had added iron and other metals to the river it would be contamination or pollution. If it is the natural process of erosion and weathering is it not also leading to contamination? Erupting volcanoes exhaust enormous volumes of toxic gases. It is natural but no less harmful?

Life and time is slow here. It feels good. I thought about time. Human history and pre-history as an instant in the vast span of geologic time.

The Volcanic Massive Sulphide deposits of the IPB formed between 360 and 345 million years ago. This was about 100 million years before the dinosaurs. To try and grasp the vast span of geological time with no vestige of a beginning you could envisage a 24-hour clock. The Iberian VMS deposits would have formed at 22 hours and the dinosaurs between 22.40 and 23.40 hours. Modern humans in the last few seconds before midnight. The Chalcolithic era (copper rock) is only a fraction of a second before midnight on our clock.

The Volcanic Massive Sulphide deposits of the Iberian Pyrite Belt form on the sea floor. In submarine extensional tectonic environments. It is where hydrothermal solutions from volcanism debouche metal sulphides onto the seafloor. The metal sulphides intermingle with volcanic and sediments. Where it settles this metallic mix can accumulate into ore deposits big and small. Deposits become mines if the tonnage and grade reaches an economic threshold. Globally, VMS deposits form in clusters and along major metallogenic belts.

The Iberian Pyrite Belt is one of these great metallogenic belts of the world. It contains one of the greatest natural accumulations of metal on the planet. It extends from near Sevilla in south-west Spain to the Atlantic Ocean in south Portugal. There are approximately 90 volcanic massive sulphide deposits in the IPB. A total of more than 1,700 million tonnes metal sulphides mined in the past and remaining in the ground. The IPB VMS deposits are iron sulphides (pyrite) with smidgins of copper, zinc, silver and lead. It is this delicate peppering of precious and base metals that makes all the difference.

The modern incarnation of mining at Mina de Riotinto starts in 1873. A Scottish entrepreneur, Hugh Matheson, and a group of investors financed construction. This gave Mina a new lease of life between 1877 and 1891. By 1925 Rio had expanded overseas into Zambia (then Rhodesia) to build new copper mines. Meanwhile Mina continued with ups and downs until 1954 when Rio sold out and it passed once more into Spanish hands. Proceeds of the sale financed new exploration companies in Africa, Australia and Canada. This global expansion transformed Rio from a Spanish copper business into a global mining powerhouse.

In 1961 Rio geologists set out across the Hamersley ranges in Western Australia to assess some iron ore prospects. They were equipped with little more than a field table and a hammer. Today Rio owns a world-class, integrated network of 16 iron ore mines, four independent port terminals and a 1,700 kilometre rail network.

Chinalco is the largest shareholder in Rio Tinto at about 15 percent equity share.

In their early 1990s book, Elizabeth and Philip: The Untold Story of the Queen of England and Her Prince, Charles Higham and Roy Morseley revealed that the firm of Baring Brothers and Rowe and Pitman handled the royal investments, which included heavyweight holdings in such firms as Rio Tinto-Zinc and General Electric. Probably a definitive History of the Rio Tinto Mines is David Avery’s 1974 book “Not on Queen Victoria’s Birthday.”

Rio Tinto is now one of the big three global iron ore miners together with Australian BHP and Brazilian Vale (formerly CVRD or Companhia Vale do Rio Doce). Rio is the second largest producer pf iron ore, just behind Vale, and together the three big iron ore powerhouses account for almost 40% of global production.

Around 82 percent of Rio’s earnings come from its iron-or division and production from the Pilbara in Australia’s Northern Territory[1]. China accounts for 60 percent or thereabouts of Rio’s revenues[2].

The global iron ore market with China’s elephant buyer at a 75 percent share of global iron-ore production colliding with the big three iron-ore producers is a possibly a case of oligopsony meets oligopoly.

When China’s economic growth falters and iron ore prices fall there is an negative impact on Rio’s share price. Rio is a play on China’s economic growth and its voracious appetite for metals.

Made up primarily of iron ore, steel is an alloy which also contains less than two percent carbon and one percent manganese and other trace elements. While this defining difference might seem small, steel can be a thousand times stronger than iron.

But heat is needed to smelt steel. Steelmaking is one of the industrial activities that contributes the most to climate change. Coal-fired smelting is a big polluter and hence the move toward high-quality metallurgical coal and non-coal smelting. Consequently the price of Met coal is at historical highs. All this will make production of steel more expensive.

In a growing circular economy steel’s true strength lies in its infinite recyclability with no loss of quality. No matter the grade or application, steel can always be recycled, with new steel products containing 30 percent recycled steel on average.

Steel is one of the great paradoxes of the energy transition. Although it is essential for renewables technology, the material accounts for about seven percent of total carbon dioxide emissions from energy use but a typical wind turbine is made of 70 to 80 percent steel.

During the last couple of weeks the steel price has been slip sliding away trying to get a foothold just under $100 a tonne. Iron ore inventories at 45 ports in China jumped four million tonnes to 146 million tonnes on Beijing’s climate-related steel production controls. Prices have also been hit by weak demand from China. Steel consumption has fallen off a cliff amid stringent controls on the Chinese property sector in the wake of Evergrande insolvency fears.

Steel prices in China have declined rapidly. Be greedy when others are fearful.

The Biden $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill will mean much more metal consumption. Some $517 billion will be deployed over 10 years, with roads, bridges and highways receiving the largest allocation at $110 billion. The $40 billion set aside just for bridges is the single largest bridge investment in the U.S. since the Eisenhower Administration. Since 2013, China has launched construction projects across more than 60 countries under its Belt and Road initiative, seeking a network of land and sea links with Southeast Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East, Europe and Africa. The EU has one of the densest transport infrastructure networks in the world of which most was constructed in the 60s and 70s – except for Central and Eastern European countries. The global financial crisis in 2008 already led to enormous spending cuts even though European post-war infrastructure, particularly bridges, is literally creaking. Covid-19 has not helped. Genoa’s Morandi motorway bridge collapsed in 2018, killing 43 people and injuring hundreds. I wrote about the Leverkusen Bridge in Germany in my blog in January 2015 – https://irusconsulting.com/the-bridge-builder-europes-decaying-infrastructure/

This week Rio Tinto has a market cap of £73 (€86.36) billion based on a 10 day moving average share price of £45. The price earnings ratio is an attractive 5.26 with a dividend of almost 11 percent. From about mid-May until mid-August Rio’s share price was range-bound around £60 per share on the back of a dizzy $200 dmt and then in July a precipitous fall to around $120 dmt after further capitulation to current levels at around $91.50[3].

Chris LaFemina an analyst at Jefferies looked at what iron-ore price would generate a price-to earnings ratio of 10, free-cash flow yield of 10%, and a ratio of enterprise value to Ebitda of five for the major producers. That iron-ore price is $86.37 dmt. Rio’s 2021 Pilbara iron ore unit cost guidance is now $18.0-$18.5 per tonne[4]. BHP and Rio’s estimated cost to mine and deliver iron ore to China is about $35 dmt.

Rio is not just all about iron ore. Rio Tinto-Alcan is the third largest producer of aluminium. Rio was the eighth largest miner of copper in 2020. In July this year Rio Tinto committed $2.4 billion to the Jadar lithium-borates project in Serbia. It is one of the world’s largest greenfield lithium projects.

S&P’s view on iron ore prices is that they will moderate but remain above historic norms for the medium term at least. For a long-term investor there seems to be a comfortable margin of safety. I expect Rio to keep generating outsize dividends.

As a disclaimer I must say that I hold Rio shares since my trip to Andalucía, and I recently bought the dip. Readers should of course do their own due diligence before buying any shares.

f you enjoyed this article and aren’t already a subscriber, you can click here to sign up to my newsletter.

[1] https://www.afr.com/chanticleer/rio-tinto-s-monster-profit-doesn-t-hide-its-problems-20210728-p58drt

[2] https://seekingalpha.com/amp/article/4457079-rio-tinto-rio-stock-market-overreacting?source=acquisition_campaign_google_premium&utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=14823831578&utm_term=128719139278%5Eaud-1457157705759:dsa-402690192841%5Eb%5E549166468285%5E%5E%5Eg&gclid=Cj0KCQiAsqOMBhDFARIsAFBTN3eIa9RqZ6kPEvQQRwo3EdOpSUJ4nDdAcAsqgzZ6H2tc0cGrA6XFU9caAlmuEALw_wcB

[3] Iron ore CFR China 62% Fe Fines.

[4] Unit costs are based on operating costs included in EBITDA and exclude royalties (state and third party), freight, depreciation, tax and interest.

Thanks John – very good and interesting as always. I spent my first 5 years as a Rio geologist in jungles and barren northern wastelands – starting salary was a wopping GBP 1400.00 – per annum! And I was mighty proud of the Company – and I do get a small pension as a result.

When I started, the Coed-y-Brenin issue (maybe one of the first of their ESG blunders) was in the papers – and I fear that they have still not learned their lesson.

I follow the story in the Balkans (for good reason as you know) – and this blog https://www.miningsee.eu/rio-tintos-past-casts-a-shadow-over-serbias-hopes-of-a-lithium-revolution/ is just one of many that they need to address – and please not with another TV ad.

Thanks Duncan, Rio has gone to an expensive school at Juukan Gorge. I think people and cultures can change. I hope so.

Great read John,

My favourite company, [or at least 5 years happily driving Land Rovers], even though my fairly short time with them did not provide any company pension. But their shares provide a healthy dividend for the poor pensioner.

Rio’s greatest contribution to popular culture? Teaching the workers at the Rio Tinto mine to play Association Football. Oops.

Chris Cooper

All the Best Chris

Slàinte Mhath

Thank you John, another informative read.

Best regards,

Alan Mooney

.

Thanks Alan